How to Avoid Overdredging

Overdredging, or dredging beyond the specified design dredge depth, is one of the most frequently misinterpreted or under-defined terms in a contract—and for owners and contractors, can be one of the mostly costly and contentious. Unlike land-based excavation that can achieve millimeter accuracies, tolerances for quantities of material removed underwater are highly dependent on survey accuracies, soil conditions, equipment used, etc., all elements that drive an operator’s ability to remove a defined quantity of material to a specified accuracy.

Understanding Overdredging

The provisions that enable successful dredge operations

Dr. Donald Hayes, Research Environmental Engineer at the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center, confirmed, “Dredging is a high risk, thin margin business. When working in a dynamic environment, there is a maximum level of precision that makes sense.” David Kinlan, Principal of Kinlan Consulting Pty Ltd., a Chartered Quantity Surveyor and Queensland Registered Adjudicator, confirmed, “The perennial issue with contract dredging specifications is a lack of detail. There will always be overdredging, but to what extent? And is that paid by the client or absorbed by the contractor?” Finding a balance begins with clear contractual expectations.

Room for Error

Dr. Donald Hayes, Research Environmental Engineer at the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center, confirmed, “Dredging is a high risk, thin margin business. When working in a dynamic environment, there is a maximum level of precision that makes sense.”

Kinlan also noted that there’s a difference between a tolerance and what’s paid as overdredging. While designers usually define design depth and maximum dredge depth the paid specified tolerance is often an afterthought with little consideration given to clarity in the Preamble of the Bill of Quantities. The Bill of Quantities Preamble establishes the definition of the paid volume.

“The mix-up,” said Kinlan, “is usually between the tolerance in the technical specification and how the measurement Preamble has been drafted. If it is the owner’s intention that overdredging quantities are to be strictly minimized (to keep within resource consent provisions, for instance), then the consequence in terms of non-payment for overdredging beyond the design depth and any overdredging allowance should clearly be spelt out.”

Simon Burgmans, Principal Dredging Consultant at in2Dredging, an international independent dredging consultancy, agrees and explains, “Certain contracts are written so that contractors do not get paid anything for dredging below the design. Other contracts pay e.g. 20cm (~8 inches) overdredging. There should be some overdredging allowance in every contract, and that allowance should be based economics of dredging now versus cost of future maintenance dredging campaigns.”

The specifications should clearly outline the amount of overdredging that is a paid volume so that there are no assumptions by either the owner or the contractor.

Case-in-point, a specification requires a one-meter dredge depth with a maximum paid tolerance of .5 meters. In this case, the contractor has to price that extra .5 meter of overdredging into the one-meter layer thickness rate. Now, if the contractor dredges to .65 meters, the extra .15 meter is definitely not paid—and the onus is on the contractor, of course, to work within the defined .5-meter tolerance limit.

Tolerances reflect equipment capabilities and operator skills as well as conditions. Kinlan added, “In the preamble for the bill of quantities or the specification, the consultant engineer has to make a determination whether the overdredging allowance is paid or excluded, which then has to be priced into the contractor’s unit rate for the dredging to the design depth.”

Burgmans added, “In the production estimate for any tender, you should always allow for overdredging. Depending on the project, a dredge can only cover so many square meters per hour. If there’s a lot of square meters to cover it can be quite time consuming. Therefore, overdredging in an earlier stage can avoid the need of covering the entire area during each dredging maintenance campaign.”

He further points out the need for calibration of survey equipment. “When a dredger mobilises to the site, they should always calibrate the system before the dredging works commences,” Burgmans said. “The contractor should provide evidence on the calibration in the existing conditions. Sometimes it’s not a matter of over or under dredging, it’s a matter of dredging inaccurately with uncalibrated system.”

A Corp Perspective

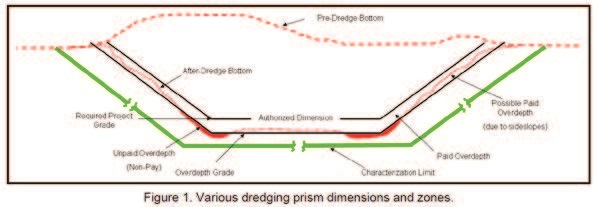

United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)1 defines paid allowable dredging as the dredging that “occurs outside the required authorized dimensions and advance maintenance (as applicable) prism” with the knowledge that there are conditions and inaccuracies in the dredging process and the specifications should reflect a “balanced consideration of cost, minimizing environmental impact, and dredging capability considering physical conditions, equipment, and material to be excavated.”

The ER 1130-2-520 (USACE 1996) provides that District Commanders may authorize dredging of a maximum of 2’ of paid allowable overdepth in coastal regions and in inland navigation channels. But it’s the characterization depth, or the maximum depth to which material can be reasonably expected to be removed, that often vary by a margin of error of less than a foot or more than several feet. Because hydrographic surveying is used to measure the depth to the bottom before and after dredging, the accuracy of the hydrographic survey is a critical component in determining characterization depth.

In the relative calm of sheltered harbors, bays, and estuaries, typical hydrographic survey accuracies of +/- 0.5 feet are achievable for a majority of the soundings at a 95% statistical confidence level. As exposure to the elements increases, so can the motion of the hydrographic survey vessel, reducing the accuracy of the individual soundings. Additionally, the water surface’s relationship to the dredge datum must be established and measured during times of surveying and dredging (USACE 2002). This is typically achieved by using a tide gage or real time kinematic (RTK) methodology. Either selection requires accurate modeling to avoid height/time tide errors. For example, if the tide gage is a long distance from the dredging area, the water surface at the dredging site can be a different elevation from the tide gage, further reducing accuracy of the hydrographic survey.

Excavation accuracy of a channel, for instance, relates to closeness of the dredge’s completed work to the design (project and/or overdepth) grade as determined by an after-dredge hydrographic survey.

There are inherent excavation inaccuracies in the dredging processes. No dredge excavates a perfectly flat bottom exactly on the required project grade. Excavation accuracy relates to closeness of the dredge’s completed work to the required project and/or over depth grade as determined by after-dredge hydrographic surveys. Dredge excavation accuracies vary as a function of the type of dredging equipment used (mechanical or hydraulic) and its respective interaction with site-specific physical conditions (tides, currents, waves), type and thickness of sediment or rock being dredged, channel design (water depth, side slopes, etc.) and level of dredge crew skill and effort. Error components introduced by the dredge’s positioning system and the hydrographic surveying techniques and equipment used to measure bathymetry will also contribute to overall excavation accuracy.

According to the USACE report, material removed from this allowable overdepth is paid for under the terms of the dredging contract. Material removed beyond the limits of allowable overdepth is not paid for—and non-pay dredging is a costly exposure. Non-pay dredging, or dredging outside the paid allowable over depth, occurs due to such factors

as unanticipated variation in substrate, incidental removal of submerged obstructions, or wind or wave conditions that reduce the operators’ ability to control the excavation head.

Environmental Constraints

Placement capacity on environmental dredging projects that deal with contaminated material is a major challenge for any dredge operators. Over dredged materials have to align with resource consents for dumping the spoil. For the permit process, owners don’t work with net volumes; they work with gross which includes over dredged materials. “Regulators need to know the total volume of material which is to be removed and set parameters in the extraction permits,” Kinlan explained. “Adequate thought must be given to the factors which may influence the amount of overdredging which may ultimately result so that the permits accurately reflect the likely dredge depth which is finally achieved.”

For instance, if a client has a disposal permit for 100,000 cubic meters, that quantity must include the paid tolerance (e.g. 90,000 cubic meters plus 10,000 cubic meter tolerance). Many contracts will define under and over dredge constraints. For example, some might say remove 10 meters (~30 feet), any more than that and the dredge operator has to pay the customer. When dealing with contaminated material, accuracy is essential. If the quantity of overdepth dredging is not properly estimated, it could lead to misleading conclusions concerning the environmental impacts that may occur at the disposal site (Tavolaro and Weinberg 2006).

In the ERDC/TN EEDP-04-37 June 2007 Technical Note (https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a470164.pdf), Tavolaro, etc., said, “There are inherent excavation inaccuracies in the dredging processes. No dredge excavates a perfectly flat bottom exactly on the required project grade. Excavation accuracy relates to closeness of the dredge’s completed work to the required project and/or overdepth grade as determined by after-dredge hydrographic surveys. Dredge excavation accuracies vary as a function of the type of dredging equipment used (mechanical or hydraulic) and its respective interaction with site-specific physical conditions (tides, currents, waves), type and thickness of sediment or rock being dredged, channel design (water depth, side slopes, etc.) and level of dredge crew skill and effort. Error components introduced by the dredge’s positioning system and the hydrographic surveying techniques and equipment used to measure bathymetry will also contribute to overall excavation accuracy.” Hays added, “The topic of precision dredging, reducing that tolerance as much as possible, is important, especially in environmental dredging. There are several issues. For example, if required to remove two million cubic yards, an owner does not want the dredge operator to remove anything more because of sediment management costs. Anything technology developers can do to improve the process and reduce excess dredging, is valuable.”

Visualization Advantage

Common practice for dredge operators around the world is to use paint marks around the dipper arm to measure quantities of dredged material. Dredge visualization systems can significantly improve real-time measurements. These solutions empower operators to dredge with greater accuracy and efficiency, and sonar integration is helping validate work completed in real-time and driving better margins. What was impossible 5-10 years ago, is not only possible today, but it’s also affordable to large and small operators , particularly when looking at ROI.

Adding a sonar to a 3D visualization system is a useful tool for the operator to access real-time feedback of the new surface, to confirm progress vs. the design. In most cases, the sonar is mounted beneath the barge, and located with offsets to align with the excavator location. The 3D visualization software can set over and under dredge limits, which are reflected on the color grid map in the cab. As the operator’s ‘eyes under water’, the sonar sensor soundings are displayed in real-time on the map in the cab, providing instant feedback about what’s removed.

Integrated 3D visualization/sonar solutions, when combined with GNSS positioning systems, replace more conventional manual methods such as tide gauges and paint marks around the dipper arm of the digger, with more accurate results. The combination could potentially save hundreds of thousands of dollars in rework, saves days, weeks and months in time and drives productivity.

“Every dredge can acquire digital data and that should be used in performance review. Both the owner and the contractor should be monitoring where the bucket goes compared to design,” said Burgmans. “If a dredge contractor is able to achieve even 1 or 2 inches more accuracy across an entire harbor or a river dredging project, that can be quite profitable especially in case of hard soil or rock.”

3D visualization systems, when incorporated on hydraulic excavators, wire cranes, bucket dredgers, underwater ploughs, trailing suction hopper dredgers and cutter suction dredgers, are able to track the dredge head. In the cab, the operator can see the planned vs. actual surface in 3D, profile and long-section views. The GNSS-enabled system provides precise position and heading of the machine and guides the operator to the desired surface and determines the cut or fill.

When asked his opinion on the role of technology such as 3D and sensors, Hayes said, “We have to move forward and take advantage of the technologies available. Dredging is an efficiency business. That’s how they make money and margins are already thin. Surveying technology has gotten better. Even positioning accuracy and ability to monitor tides in real-time has come a long way. It will be interesting with better equipment. I believe operators will be able to routinely achieve 6 inches as a realistic overdredge in most conditions.”

No matter the technology available, Kinlan reinforced the importance of the contract. “The contract drafter should consider whether overdredging is paid as a measured quantity to the overdredge allowance or to be absorbed in an allowance in the Contractor’s unit rates and prices. There is no industry standard or guideline in this respect. Each dredging project should consider the merits of a paid or unpaid dredging tolerance. A well-defined overdredging provision in both the technical specification and Bill of Quantity Preamble clause will result in less chance of misinterpretation of how the overdredging allowance is to be applied by the owner.”

Solid words of advice as the proposed infrastructure bill in the U.S. alone includes some $22 billion in port and waterway improvements.

Do you have questions about this case study?

Get in touch with Trimble Marine Construction, and they would be happy to answer any questions you have about pricing, suitability, availability, specs, etc.

Related products

![Do-Giant-Tortoises-Make-Good-Neighbors-1[1].jpg](https://cdn.geo-matching.com/vRMO2Edp.jpg?w=320&s=a6108b2726133ff723670b57bc54c812)